Rugby Player & Team Selection Process

What is a rugby player / team selection process?

The selection process for any player is always challenging, but it’s arguably a coach’s most crucial role.

The key is communication, mainly keeping connected to a player if she is not selected, explaining why he is in or out of the team, and giving him “work-ons” and roles to feel part of the group still and contribute to it.

Similar to other sports, selecting a rugby team involves creating a consistent selection process based on an established set of prioritised positional criteria that, when implemented, should enable the team to deliver its game plan.

Examples of selection criteria are:

- Players that are good at using a “blitz” defence.

- Players with competency to win the ball at ruck.

- A player than can kick penalties well.

- Players with good catch and pass skills.

- Players with high levels of physical conditioning.

What is a good selection methodology?

There are various methods you can use when selecting players for a rugby team. For example, with a junior rugby team of 10 year old players, it may be a simple case of selecting whomever needs game time. For some teams, it’s about finding enough players on a Saturday morning to make a team!

The following framework is better suited for coaches that manage senior rugby teams with enough players to select from. Nonetheless, we recommend that all coaches have a proper selection process, even at a junior level, as it helps foster player engagement, better execution of your game plan and better management of players and parents nagging for more game time!

Here is a quick overview of the selection process:

Player selection is not done in isolation, it needs to connect with other important processes, such as your game planning process, as selecting the wrong players would impact directly on the execution of your patterns of play.

The following four-step player selection process assumes you have set your game plan and are now looking to select your squad of players for that game.

Step 1: identify the key functional roles (actions) a player needs to perform in each position, during set piece and open play.

Step 2: define the outcomes for the key functional roles.

Step 3: list in priority order the key actions that will result in the outcomes being achieved.

Step 4: select the players (see next section).

Example Player Selection Form

| Position: | Player's Name: | Date: |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Roles in priority order | Outcome per functional role | Key factors to achieve the outcome |

| 1. | ||

| 2. | ||

| 3. | ||

| 4. | ||

| 5. |

Select players by using the Patterns of Play

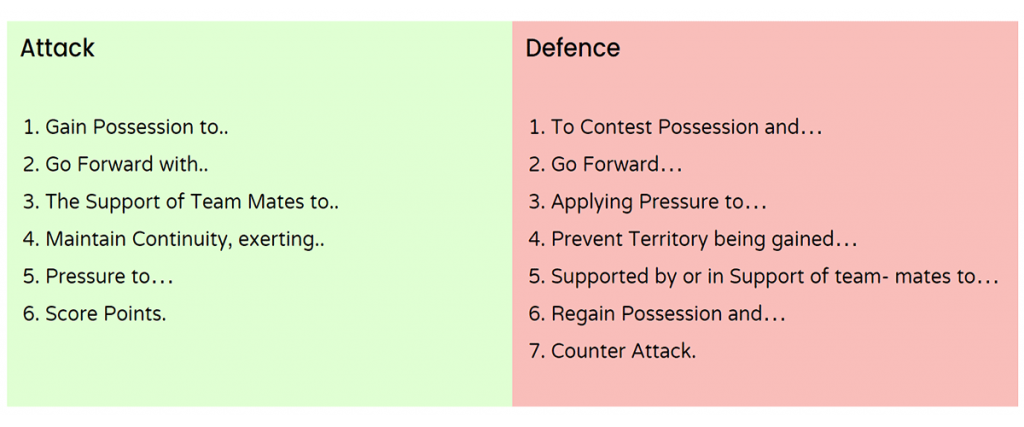

The players you select are a reflection of how your team plans to implement it’s attack and defence patterns of play for any given game. The player selection process is thus a key influence on other aspects of a coach’s game planning process and the outcomes you want to achieve.

For example, selecting a powerful, less mobile front row rather than a less powerful more mobile front row, directly influences your patterns of play and game plan.

Observing Rugby Players for Selection

At an amateur or junior level, you probably won’t have the resources available to follow the selection process outlined below. Bear in mind, a robust selection framework helps cover resource gaps.

Observe from a selection point of view and not from a coaching point of view.

With more advanced teams, when selectors are watching players they must be constantly referring to the positional requirements they are to concentrate on. This task is different from coaching. The selectors are watching individual players. They should not be distracted from this by watching the match as a whole. This takes considerable discipline.

Experience has shown that individual players should be watched constantly for up to 10 minutes. This would seem to be the minimum period. The selector must be able to observe play during the following two scenarios:

- when the player is away from the ball

- when the player is directly involved in using, retaining or regaining the ball

This is more important for some positions than others.

You may have noticed even selectors of international teams watch live games when observing a player. You can, if available, watch videos of a player – though a video tends to provide a narrow snapshot of a player as the camera follows the ball, not the player.

When a selector is watching a player the positional requirements are a checklist to categorise information. All information should be recorded. This may be done by, writing it down, however, play can be missed while this is being done. A better method is to use a dictaphone. This can be replayed a number of times after the match.

Both written notes and recorded information must be compared to the positional requirements. This ensures that each player for each position is compared using the same criteria. Selectors should watch players independently. This is to ensure they don’t fall into the trap of supporting each other’s point of view.

A major difficulty when selecting is reducing the number of players being watched so each can be watched for some time. The categorisation of players into the “in”, “out” and “unsure” groups achieve this (some coaches use a red, yellow, green traffic light system too). It enables selectors to concentrate on a limited number. This is a worthwhile method, however problems arise when players take part in trials.

Prior to the naming of trial teams, a considerable amount of work will have to be done gathering information on players. In a trial, comparisons can be made between two players competing for the same position. The difficulty is that there are 15 positions, all of which may have to be observed. Clearly this is impossible to do thoroughly but it can help to play against an opposing team that is not in contention for selection. It reduces the number of players to be watched by half, but it is difficult to make comparisons.

At representative level and above, the problem may be solved by increasing the number of selectors for the trials only. The most obvious way would be to have a selector for each position. This would involve eleven selectors. Where there are two players playing in a position there will still be time enough to watch each player for at least 10 minutes. This frees the official selection panel to watch specific individuals, as they will know that there are selectors covering all positions.

For this to work successfully, the positional selectors have to be briefed in detail about the positional requirements. Once the trial is over, a debriefing of the whole group should take place before the official panel is left to make their final selection.

This system works well so long as the positional selectors are well chosen, understand what is required and are disciplined to watch the players rather than the match. When this is first done, all positional selectors may not be able to meet these criteria. However, at each successive trial the standard will improve as they become familiar with what is required. Changes may have to be made before someone who is good at positional selecting is found.

A good selection process motivates players

A final thought, albeit an important one.

Using an objective, standardised method for selecting players enables a coach to provide a player with objective, constructive feedback on what they are doing well and where they need to improve to make the squad, the team or the starting 15.

Constructive feedback is a lot more motivating to a player than not receiving feedback or getting ad hoc feedback. All coaches, in particular at an amateur level, need more players – providing feedback in particular when it comes to selection, is a key opportunity to drive player engagement and buy in to your plans.

Ideally, you want to provide feedback to a player(s) using models such as the BOOST model below:

- Balanced. The good and the not so good.

- Objective. Be objective and constructive, rather than belittle a player.

- Owned. Your feedback, not what someone else thinks.

- Specific. Provide specific feedback with examples.

- Timely. Provide feedback at the right time and the right place. Some players will be sensitive about receiving feedback, especially if it is negative feedback.

Overlap between Player Selection & Session Planning

There is a lot of overlap and synergy between player selection, planning your sessions and executing your game plan. Click the link below to read more about planning your practice sessions.